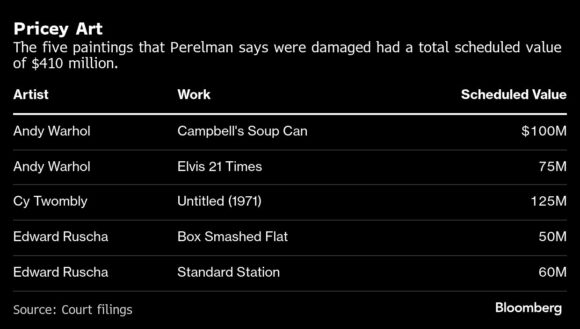

Nearly seven years after a fire swept through Ron Perelman’s Hamptons estate, he is urging a New York state judge to compel insurers to pay over $400 million for five artworks he claims were affected by the blaze.

The trial commenced today in lower Manhattan regarding a lawsuit Perelman filed two years post-incident. According to the suit, subsidiaries of Lloyd’s of London Ltd., Chubb Ltd., and American International Group Inc. provided policies that “insured one of the world’s largest private collections of modern art against any level of damage” — yet refused to pay for some of the most valuable artworks in the home. These included notable pieces by Andy Warhol and Cy Twombly.

This case offers a rare view into the secretive realm of high-end art collecting and the often-private battles between wealthy collectors and their insurance providers, who usually settle out of public view to maintain confidentiality around collection details.

The trial — where Citadel founder Ken Griffin’s deposition may be presented — is also expected to reveal insight into the current financial status of Perelman, once regarded as the richest man in America, whose net worth has declined significantly in recent years. His most prominent business, Revlon Inc., filed for bankruptcy in 2022. Testimony disclosed that he sold nearly $1 billion in art after collateral tied to the company dropped in value and lenders demanded repayment.

Perelman’s attorney, C. Bryan Wilson, argued in his opening that the insurance agreements entitled Perelman to claim the full insured value — which in some cases exceeded market value — even for minor damage. He stated the insurers were eager to collect premiums, but later backtracked when faced with a substantial payout.

“It Was Raining Inside”

“It was essentially raining inside the house” as fire crews battled the blaze, Wilson said. The five disputed artworks were relocated multiple times during the cool, damp night and remained in high humidity for more than 12 hours. Wilson explained to Justice Joel M. Cohen, who is presiding over the bench trial, that insurers had compensated for damage to over 30 other works — 11 of which were on the same floor as the disputed paintings.

According to Wilson, the insurers later “regretted the agreement” and arbitrarily “drew a line in the sand.”

On the other hand, the insurers describe the suit as a cash grab, arguing that Perelman failed to show the artworks were harmed. They point out that two of the pieces later purchased by Griffin were located near the disputed works during the fire — and suggest that if Perelman tried to sell them, it may indicate he didn’t believe they were damaged. Griffin is not directly involved in the case, but his testimony is part of the evidence and may be introduced during the trial.

In his own opening statement, Jonathan Rosenberg, counsel for the insurers, told the court that Perelman submitted the claim while grappling with “serious financial trouble” and looming margin calls, emphasizing his substantial art sales.

“Kitchen Sink Approach”

“He throws in everything but the kitchen sink,” Rosenberg said. “He’ll admit he had no knowledge of actual damage when the claim was filed — it was financially motivated.”

According to Judith Wallace, managing partner at Carter Ledyard & Milburn and chair of its art law practice, the case stands out due to both the extent of the damage and Perelman’s profile. “He’s also known to be a formidable and well-funded litigant,” she noted, adding that “each side is likely to advocate very aggressively.”

Wallace explained that art insurance policies often include dispute resolution clauses resembling arbitration, which are almost impossible to challenge in court unless fraud can be proven.

Wealth Collapse

Perelman’s holding company, MacAndrews & Forbes Inc., once owned major names like Marvel, Coleman, and New World Entertainment. It currently holds interests in two biotech firms and Vericast, a financial services company that underwent debt restructuring last year. Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index estimated his net worth at $19 billion in 2018, falling to $3.3 billion by 2021 when tracking ceased.

The trial is expected to run for about three weeks and feature testimony from Perelman, a Brooklyn-based framer who worked on the paintings, and expert witnesses including chemist Jennifer Maas for the plaintiff and conservation engineer Marion Mecklenburg for the defense.

The $410 million claim stems from a 2018 attic fire at Perelman’s Hamptons estate, the Creeks, which caused destruction to parts of the property, including art and furnishings. While insurers paid over $100 million for the damage, the five artworks in dispute — which were stored in glass-like frames and showed no immediate signs of harm — weren’t part of the original claim, although staff noted they were under observation. They were reinstalled at the estate in the summer of 2019.

Perelman’s policies were structured to cover much more than market value, allowing him to replace damaged pieces with works of similar caliber regardless of resale intentions. Unlike typical policies that only reimburse for repair costs, his agreements permitted full-value compensation for replacement.

One disputed piece, Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can, was insured at $100 million, though appraised at $12.5 million in 2018, according to court records.

The case is AGP Holdings Two LLC v. Certain Underwriters at Lloyd’s of London, 654742/2020, New York State Supreme Court, New York County (Manhattan).